Gazing at the lush green leafy trees on a popular street of Almaty, the biggest city of Central Asia’s largest country Kazakhstan, Daverbek Kadiraliev, said to me: “Yes, I want to go back and live in my country but our lands have died, our fields have turned into deserts, water is life and we are without water”.

Hailing from the Andijan region of the Fergana Valley in Uzbekistan, one of the five landlocked Central Asian states; Daverbek is among hundreds and thousands of climate migrants who started leaving Uzbekistan when water scarcity started destroying centuries-old lively hoods.

Officials privately admit that over four million Uzbeks have left the country since Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991 following the split of the Soviet Union. Water scarcity forced thousands of Uzbek citizens to leave for Russia, Kazakhstan, South Korea and other countries in search of work where many of them work illegally.

Daverbek studied textile engineering technologies. By the time he completed his education, the Uzbek textile industry was in crisis because of water shortages. Due to the unstable policy on the use of transboundary rivers, most of the fields have become unsuitable for growing cotton. Instability in relation to the use of international water resources has been further exacerbated by climate change.

Twelve classmates of Davrbek out of twenty became labor migrants, and today only two work in Uzbekistan in their specialty. Everyone else had to change professions, adapt to a separate life from the family and from the homeland.

Cotton, Uzbekistan’s main cash crop, is an extremely water-intensive crop. The two main rivers of Central Asia, the Amu Darya in the south and the Syr Darya in the north, irrigate cotton fields in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

“Earlier in Uzbekistan, every family had a garden where they could grow the crops they needed for their needs, but now everything in the houses dries up due to lack of water. The canals disappeared, the cities became sway and “gray”, people began to get sick often,” says Davrbek.

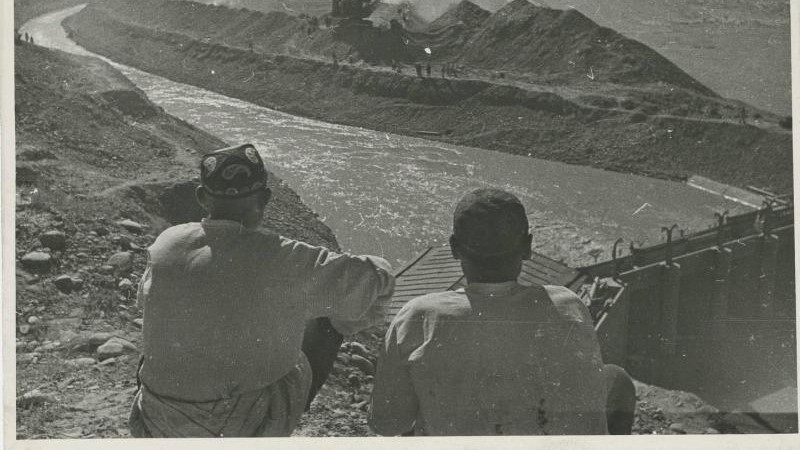

Some of Central Asia’s cotton growing fields were parts of the Mirzachol and Kyzylkum deserts before the cotton cultivation. The Soviet government constructed a canal system that diverted water from the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya to deserts transforming them into cotton fields. These are cotton-producing regions and home to cotton-related industries in present day Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

The Soviet Union was the second-largest cotton producer in the world. At that time, nearly 80 percent of Uzbekistan’s 24 million population depended on cotton production and related industries. Uzbekistan is now the fourth-largest producer of cotton and less than 50 percent of the country’s 37 million population depend on cotton for a living. The government is diversifying the economy but cotton is still a priority. To save cotton, the government has been diverting water from other crops to cotton fields.

The five Central Asian States- Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan—share rivers and have been struggling to resolve water shortages and water distribution issues since their independence in 1991. The problem is complicated because in some areas, the state boundaries are not demarcated.

The Amu Darya originates in the Pamir Mountain range in Tajikistan in the South, and the Syr Darya’s mouth is in the Tian Shan mountains in Kyrgyzstan. Downstream countries Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and to a lesser extent Afghanistan use water from these rivers through irrigation canals.

Mountain glaciers are the major source of water in Central Asian rivers. Tajikistan used to have 13000 glaciers but nearly 25 percent of the glaciers have melted in the past 70 years and another 25 percent could disappear by 2030.

Water flow in the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya has been decreasing due to an acceleration in glacier melting caused by rising temperatures and less snow fall, intensive use of water through irrigation canals and the construction of reservoirs in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Roghun Dam on the Amu Darya in Tajikistan, for example, will be the world’s tallest dam (335 meters high). It is expected to be completed by 2028 and will have a capacity to generate 3600 MW of hydropower. This will solve Tajikistan’s electricity shortage problems but will cause a further decrease in water in the Amu Darya, which used to fall in the Aral Sea, but no longer. The River dries before its final destination. Consequently, 2/3 of the Aral Sea has gone though Kazakhstan has managed to restore a part of the Sea.

All Central Asian states are heavy water users. Most of the water is used for irrigating the cotton crop. While Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are the least water-stressed countries, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are the most water-stressed states.

Along with climate change and extensive irrigation, the poor management and weak inter-state cooperation have created the water crisis in Central Asia that might cause food security problems, mass migration, and even conflicts.

Kazakhstan the largest and economically strongest among the five Central Asian states has been leading efforts to overcome the water scarcity issue in Central Asia by searching for scientific solutions.

Kazakh National Agrarian Research University (KazNARU), is one of Kazakhstan’s oldest universities. KazNARU hosts an international research center, “Water Hub” with 14 research laboratories dedicated to water and water research. Water Hub is Central Asia’s only and the most modern water research facility. The University’s Rector Professor Tlektes Yespolov, a prominent water expert, has been leading a team of experts that is drafting a new ‘Water Code’ for Kazakhstan. The new Code emphasizes water conservation and offers incentives for economical water use.

“We must treat water for its economic value and consider it as a product. For example, each used cubic meter of water in Japan brings 53.5 USD and 23.5 USD to the United States. But in Kazakhstan water brings only 8.7 USD,” says Professor Yespolov.

Kazakhstan, too, is a water-deficient country. The World Bank has estimated that the level of water stress is 31% in Kazakhstan.

Professor Yespolov says that nearly 40% of Kazakhstan’s water resources originate outside its territory. Up to 90% of the annual runoff of steppe rivers occurs in the spring season, and up to 70% of the runoff of mountain rivers takes place in the summer.

“Weak international interaction and cooperation with countries in the upper reaches of transboundary rivers may have consequences for Kazakhstan therefore enhancing regional cooperation regarding shared water sources is crucial,” noted Professor Yespolov.

Scientists estimate that the “greenhouse effect” and climate change, as well as the withdrawal of additional flows of transboundary rivers by countries such as China, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, might reduce the average annual volume of water to 85 km3 a year in Kazakhstan in the future. This reduction in water volume would have an impact on irrigation agriculture in the country.

KazNARU Water Hub researchers have carried out long-term studies on climate change and its impact on water resources. The study found that the air temperature throughout Kazakhstan has been gradually increasing from year to year. For example, the average annual temperature in Almaty 100 years ago was about 7 °C, and today it is 12 °C (an increase of 5 degrees).

Water Hub and the Kazakh Research Institute of Water Management scientists have jointly developed energy-efficient reclamation technologies. They are also collaborating with the Institute of Geography and Water Security in developing strategies to overcome the water scarcity problem in the Central Asian region.

In their report, the scientists have recommended a decrease in the number of water-intensive industries; introduction of modern water-saving technologies in the industry, agriculture, housing, and public services, and increasing freshwater resources through interstate water relations, regulation of river flows, use of groundwater reserves, desalination of saline and brackish water, an artificial increase in precipitation, and territorial water redistribution.